Renewed Push for Four-Day Workweek Gains Momentum Amidst Technological Advancements and AI

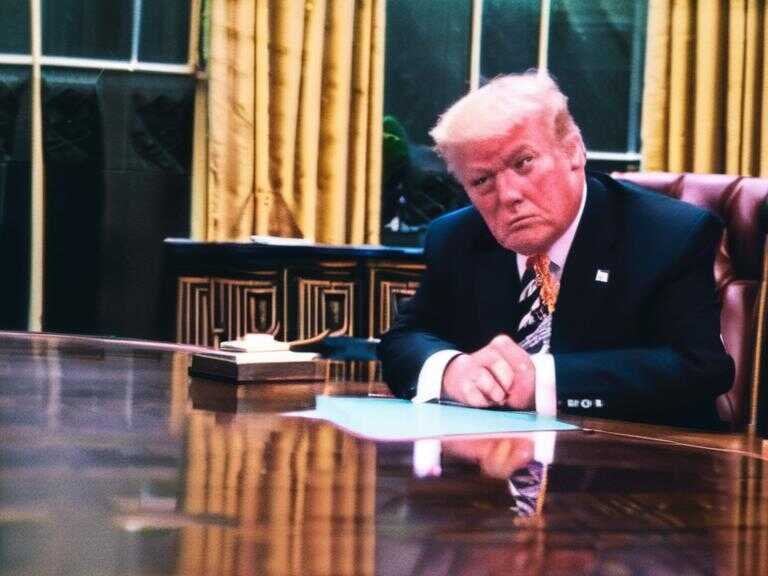

A global crisis in 1956 sparked talk of a four-day workweek, mirroring today's debate. Early advocates included Richard M. Nixon.

In 1956, then-vice president Richard M. Nixon (R) proposed a radical idea: a four-day workweek. However, this was not the first time that such a concept had been raised.

Early Predictions of Reduced Working Hours

Even before Nixon's proposal, economist John Maynard Keynes had predicted that technological advancements would make a 15-hour workweek possible by 2030. American founding father Benjamin Franklin had also foreseen a future where four hours of work a day would be sufficient. These predictions set the stage for a renewed push for reduced working hours, which has deep roots in the labor movement and the rise of technology.

The Labor Movement's Struggle

The battle over working hours dates back to the 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution led to longer working hours for many. Despite the expectation that increased mechanization would result in fewer working hours, workers found themselves facing grueling 14- to 16-hour shifts, six days a week. The push for fewer working hours became a key issue for early union efforts, with demands for "eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will."

While Henry Ford famously instituted an eight-hour-a-day, five-days-a-week work schedule for his Ford Motor Company employees in 1926, it wasn't until 1938, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt (D) signed the Fair Labor Standards Act into law, that the 40-hour workweek became widely implemented. However, after the establishment of the 40-hour workweek, the push for shorter shifts became a divisive issue within the labor movement.

Technological Advances and Political Backlash

Following World War II, the United States experienced a surge in productivity and technological innovation. However, the rise of automation sparked concerns about machines taking over jobs. Despite early hopes for more leisure time through new technology, the reduction in the size of the labor movement and its power led to a shift in the political landscape. With unions losing power, politicians backed away from the question of reducing working hours.

Nixon's Abandoned Vision

By 1960, just four years after Nixon's proposal of a four-day workweek, the then-presidential candidate retreated from the idea during a national telethon campaign event. Nixon cited the lack of efficiency in reducing the workweek due to the practices of business and labor, stating that it "just isn't a possibility at the present time."

Challenges and Changes in the Workplace

Despite periodic waves of excitement over new technologies, the implementation of these changes in the workplace unfolded over a longer period. While progress in reducing working hours came in the form of vacation and other paid time off, the labor movement's decline and rising unemployment in the 1970s made bargaining conditions more challenging for workers.

Consequently, most reductions in the workweek came through collective bargaining rather than legislation. Unemployment rose, and competition with other countries intensified, further contributing to the difficulties in pushing for a shorter workweek.

Modern Push for a Four-Day Workweek

While the labor movement has not regained its previous strength, a renewed push for a four-day workweek is gaining momentum in the modern era. Unlike the mid-century, the current drive for a four-day workweek is not primarily led by blue-collar and union workers, but rather by white-collar and corporate employees. The focus is on achieving better work/life balance and promoting a stronger sense of community.

Despite the challenges and changes in the workplace, the idea of a four-day workweek persists, offering a glimpse into a potential future with reduced working hours and improved well-being for workers.

Share news